Mixed Emotions

Consolation, Anger, and a Boys’ Choir in Berlin, 1887

by Joseph Ben Prestel

On January 5, 1887, the head of Berlin's 42nd police district, Lieutenant Laiber, sent a comprehensive report about the performance of a boys' choir in the neighborhood of Kreuzberg to the city's police department. Laiber wrote that a constable called Werner from his district had been called to a tenement house on Prinzessinensstraße at 10 in the morning. According to the report, the constable discovered that eight boys from a choir were performing Christian songs in the courtyard of the building. He noted that the choir leader, a certain Friedrich Marquardt, was absent during the performance, delegating the leadership of the choir to a fourteen-year old schoolboy. The report stressed that the performance without adult supervision had turned into a nuisance:

The boys nudged each other on purpose and some of them laughed out loud during the performance. They also collected coins that inhabitants of the house had thrown on the courtyard. Moreover, the sacred songs were sung in such an unharmonious and incomprehensible fashion that the singing resembled blasphemy and the inhabitants [of the tenement house] expressed their sorrow about such an activity.1

Following this report, the police department contacted Friedrich Marquardt about the event. In its letter, the police department repeated the allegations made by the constable and the head of the 42nd police district. Moreover, the letter stated that the intended positive emotional effect of the choir's singing had been perverted: "Instead of exhilaration [Erbauung], the audience could only experience anger."2 The police department threatened to revoke Marquardt's permission for public performances if the choir performs again "without the guidance of an adult" and if these "improprieties" continue.3 Friedrich Marquardt responded to the allegations by assuring the police that performances without an adult leading the choir would be an absolute exception. Marquardt had merely intended to join the choir later in the morning. In addition to this clarification, Marquardt provided a different account of the choir's performance on January 5 and its emotional effects. According to Marquardt, the choir was sent to the tenement house on Prinzessinenstraße in order to sing a New Year’s song. He stressed that this song was well rehearsed and that the choir was able to sing it without an adult choir leader. In fact, Marquardt claimed, the boys had performed the New Year's song on this morning to the "full satisfaction" of the inhabitants of the tenement house, as the landlord had assured him in a statement. Then, however, a woman living in the house came forward with a special demand:

Due to a case of illness in her family, the housewife was aggrieved and asked [the choir] to sing the song Harre meine Seele. The alto singers, however, immediately felt uncertainty in their voices, because they did not carry song books with them and they refused to sing initially. As the woman and her daughter have stated, this led at the beginning of the song to a bit of anxious talking and pushing among the boys. Also, during the song, some singers pushed others who were singing incorrectly and they laughed a bit. Yet they performed the whole song in its melody without offense and in a way that the whole family was sincerely consoled, as they assured [to me]. The family is explicitly grateful.4

Marquardt further explained that only those people, who were unhappy that an infamous drunkard no longer sang in the courtyard ever since the boys' choirvisited the house, were speaking of "anger instead of exhilaration."5 Ultimately, the police department chose to believe Friedrich Marquardt and his Protestant boys' choir was allowed to continue performing in the courtyards of Berlin's tenement houses. As a lesson from the case, however, he was obliged to request permission for each choir leader who accompanied the groups of his pupils during their performances.6

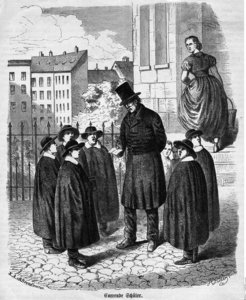

The present source sheds light on the performances of protestant boys' choirs in late nineteenth century Berlin, which formed a central component of contemporary religious interventions in working class neighborhoods and shows how conflicts about emotions could emerge in this context. Friedrich Marquardt founded his boys' choir in 1852, when he was a pastor and teacher at a school for imprisoned boys in Berlin. By trying to restore the Protestant practice of wandering boys' choirs called Kurrende, Marquardt hoped that the choir would educate his pupils while also reviving what he called "the popular spirit of religion" in the city.7 During the first years of its existence, the choir performed in two different contexts. In order to raise money, Marquardt's Kurrende appeared in front of upper class inhabitants of the city who donated to the choir. The group also ventured out into the city and sang Christian songs in the courtyards of tenement houses in Berlin's working class neighborhoods. With its mission of spreading a religious spirit, Marquardt's project was part of a number of Protestant initiatives that emerged after the middle of the nineteenth century in order to fight a perceived decline of religiosity in Berlin. Emotions played a pivotal role in this development. As Bettina Hitzer has shown, different projects, ranging from care for "fallen" women to door-to-door visits in working class neighborhoods, aimed to provide a "Christian-Protestant net of love" in the German capital. This net of love was intended to especially prevent new arrivals and working class Berliners from falling into the traps of immoral love, criminal endeavors, and revolutionary thoughts.8 Singing was described in this process as an important means of accessing the "hearts" of the populace. The Berliner Stadtmission, one of the most influential actors among the Protestant initiatives for religious revival, portrayed its own wandering boys' choir in a magazine article as spreading an emotional wakeup call in the cold dark of the metropolis. The article noted that “good and holy songs exercise a lot of power (...) over people's hearts.”9

While Marquardt cooperated with the Stadtmission, he kept his choir independent. Marquardt was also in regular contact with the police department, as the trade regulations from July 1883 stipulated in paragraph 33b that those who want to offer "musical performances (...) from door to door, on public roads, streets, and squares need the prior permission of the local police authority."10 In his request for permission from the police department in 1885, Marquardt described the purpose of the choir in an emotional language that was similar to the claims of the Stadtmission. According to Marquardt, he had started to work with children from a working class background because of his "love for the youth of Berlin's proletariat."11 Despite his message of love, however, he indicated that the choir first needed to win over urban dwellers. One should not expect, Marquardt noted, that the inhabitants of tenement houses would show an automatic "willingness" to let his Kurrende perform in their courtyards. Therefore, the choir had to give listeners a short sample of its music first with the aim of making people "find pleasure in the singing."12 Marquardt's statement hints at the emotions that the Kurrende could evoke, and which came to light during the performance in January 1887.

While the complaint against the performance on Prinzessinnenstraße in January 1887 did not have long-lasting effects for all protestant boys’ choirs in Berlin, the police record about the incident highlights the centrality of claims about emotions in the everyday interactions between Protestant initiatives, local inhabitants, and the police. The source reflects two different narratives about emotions in the performance. In the first narrative, which was presented by the head of the 42nd police district, the singing produced anger and was a nuisance. The reaction of the police to this incident shows that certain emotions were deemed highly problematic for public spaces. As Thomas Lindenberger has shown in his study of street politics in turn-of-the-century Berlin, the city's police was concerned with a variety of practices that were associated with the working class' disturbance of "peace, order, and security" on the streets.13 The connection some contemporaries saw between public expressions of anger in working class neighborhoods and the risk of violence is also reflected in newspaper articles that followed infamous riots on Blumenstraße in 1872. The Berliner Gerichtszeitung, for example, commented that under the current circumstances only a small "spark" was needed to ignite an "explosion of violence" on the streets of the city.14 In light of such interpretations, it was imperative that the state curbed nuisances and expressions of anger in public spaces in order to avoid crowds, unorderly behavior, and riots. Regardless of the intention of Marquardt's choir, the claim that the singing in the courtyard evoked emotions such as anger jeopardized the police's acceptance of the choir's activities.

Friedrich Marquardt himself implicitly acknowledged that the choir should avoid causing anger. At the same time, however, he provided a different narrative about the performance. While admitting that some inhabitants of the house on Prinzessinnenstraße might have gotten angry, he emphasized that a number of people had expressed feelings of satisfaction and consolation. In Marquardt's telling, his choir was not only imbued with a message of love, but also responded to the emotional demand of the inhabitants of the tenement house, namely the need for consolation in grief. Marquardt's earlier correspondence with the police department illustrates that this claim to spread "positive" feelings was not only central for his own self-representation, but was also critical for obtaining the permission for his choir to perform in the courtyards of Berlin's tenement houses. The case from January 1887 thus illustrates how Protestant initiatives for religious revival in the city negotiated the emotional impact of their activities in the public realm with the police.

Ultimately, this source also provides information on the inhabitants of the tenement house. While these actors were not directly involved in the writing of the police record, the document offers plausible hints of their participation in the conflict. Since the police were called to the building on Prinzessinnenstraße, local inhabitants seem to have actively contributed to the accusation that Marquardt's choir triggered anger. This observation is further strengthened by the fact that Friedrich Marquardt acknowledged that some listeners might have felt angry. Furthermore, Marquardt's remarks suggest that the choir was met with anger on other occasions as well. The choir leader's explanation of the incident was based on the claim that local inhabitants demanded a song to be consoled. While it is impossible to gauge whether the choir sang Harre meine Seele truly in response to a request by grieving family members or whether Marquardt simply fabricated the story, his account seems at least to have been plausible enough to be accepted by the police. The police record therefore suggests that some inhabitants of the building in Kreuzberg expressed anger at the performances of the Protestant boys' choir, while others might have seen the choir as a way of overcoming grief.

Other sources show similar emotional confrontations between local inhabitants and Protestant boys' choirs. A police record from 1899, for instance, contains a report from two police officers describing how a performance of the boys' choir of the Berliner Stadtmission on Luisenstraße resulted in a crowd of more than one hundred people making jokes and insulting the singers.15 Drawing on these police records, a history of emotions can contribute to a variety of research contexts in German history. Above all, these sources demonstrate how emotions were an important part of the negotiation of "peace and order" in public spaces between the police, local inhabitants, and Protestant initiatives. In order to be tolerated by the authorities, Protestant initiatives had to make sure that they were not seen as provoking dangerous emotions among the populace. Moreover, these police records demonstrate the role of emotions in the interactions between inhabitants of tenement houses and the Protestant clerics that entered working class neighborhoods to counter the perceived decline of religiosity in the city. The mixed emotions, ranging from anger to consolation, suggest that local inhabitants showed an ambiguous response to these activities. The source described here can therefore not simply be read as reflecting either "dominantion" or subaltern "resistance." Instead, the police record suggests a repertoire of emotions in working class neighborhoods that could accommodate as well as counter the emotional message of protestant initiatives. It thus sheds light on what historians have recently begun to frame as the emotional culture of the working class milieu in Imperial Germany.16

Notes

1 "Report from January 5, 1887," Die Kurrendesänger der Berliner Stadtmission, LAB, A Pr. Br. Rep. 030, Nr. 18683.

2 "Letter from January 13, 1887," Die Kurrendesänger der Berliner Stadtmission, LAB, A Pr. Br. Rep. 030, Nr. 18683.

4 "Letter from March 9, 1887," Die Kurrendesänger der Berliner Stadtmission, LAB, A Pr. Br. Rep. 030, Nr. 18683.

6 "Letter from March 19, 1887," Die Kurrendesänger der Berliner Stadtmission, LAB, A Pr. Br. Rep. 030, Nr. 18683.

7 "Letter from August 26, 1885," Die Kurrendesänger der Berliner Stadtmission, LAB, A Pr. Br. Rep. 030, Nr. 18683.

8 Bettina Hitzer, Im Netz der Liebe: Die protestantische Kirche und ihre Zuwanderer (Cologne: Böhlau, 2006), 4.

9 Max Braun, "Die Berliner Kurrendeknaben," Bilder aus der Stadtmission 11 (1911), 6.

10 "Gesetz, betreffend Abänderung der Gewerbeordnung," Deutsches Reichsgesetzblatt 15 (1883), 160.

11 "Letter from August 26, 1885," Die Kurrendesänger der Berliner Stadtmission, LAB, A Pr. Br. Rep. 030, Nr. 18683.

13 Thomas Lindenberger, Straßenpolitik: Zur Sozialgeschichte der öffentlichen Ordnung in Berlin 1900 bis 1914 (Bonn: J.H.W. Dietz, 1995).

14 "Stadtgericht," Berliner Gerichtszeitung, October 19, 1872.

15 "Letter from June 30, 1899," Die Kurrendesänger der Berliner Stadtmission, LAB, A Pr. Br. Rep. 030, Nr. 18683.

16 See for example the report on Bettina Hitzer's contribution at the conference "Neue Perspektiven auf die Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung": Yves Clairmont, "Tagungsbericht Neue Perspektiven auf die Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung," H-Soz-u-Kult, accessed March 28, 2014.