"Oh time, oh time! Why did I waste you?"

A Nightmare

by Margrit Pernau and Max Stille

Guzra Hua Zamana ("Bygone Time") is a story on the deep anguish felt about the irreversible loss of time.

“During the year’s last night, an old man sits alone in his dark house. The night is frightening and dark. Clouds are fanning out, lightening glitters restlessly and it thunders. The storm blows with great force. The old man’s heart trembles and his breathing is irregular. The old man is extremely sad. However, he is not sad because of the dark house, nor because of his loneliness, nor because of thunder, lightnening or the raging storm, nor is he sad because it is the year’s last night. [The reason is] that he thinks of the bygone time. The more he remembers, the sadder he becomes. He covers his face with his hands and tears start to float from his eyes.“

The old man regrets to not have valued his time until it was too late. He thinks of his childhood, when he had angered his father and saddened his mother. Recalling his loveless and uncompassionate behavior towards his dear ones tears his heart apart. Even remembering his pious actions during his mature years does not calm his heart, as he reckons that deeds of worship will not endure. But when the storm in front of his window calms down, a beautiful maiden appears who introduces herself as the immortal goodness. She tells him that "whoever wants to conquer me, has to strive to do well to mankind, or at least to his own community, with his heart, life and wealth." After a ray of hope, the old man despairs again. He sighs "Alas! I would give ten thousand Dinars if the time came back and I could be a young man!", and loses consciousness.

But all of this was but the dream of a boy, who awakens to the soothing voice of his mother. Realizing he had only been dreaming, the boy exclaims: "Ah, this is my life's first day! I will not end as the old man did. I will certainly marry the maiden, who has shown my her beautiful face and told me that her name is the 'immortal goodness!'" The essay closes with an auctorial comment that urges the youth to take the boy as a model and strive for the well-being of their community.

Originally published in 1873, the essay is read widely until today. It is part of Urdu textbooks in Pakistan. In an audio-book version distributed widely in the internet, the synesthetic experience of the stormy night is enhanced by sound effects of rain, storm and thunder. The speaker furthermore adapts his voice to the old man’s despair when exclaiming "alas, time!" Just four months ago, a nearly complete English literary translation of the story by an Urdu-speaking student at King Abdul Aziz University was printed in an English-language newspaper from Saudi-Arabia and applauded by its Urdu-speaking readers, most likely migrants from South Asia – the text obviously continues to speak to contemporary readers.

At the same time, it remains a fascinating source for a historical investigation of feelings. It tells us about the emotional universe of the time when it was first written, about emotions felt, emotions desired and strategies of evoking emotions. Saiyid Ahmad Khan, the author of the story, was born in 1817 to a family belonging to the lower nobility of Delhi. His formative years saw the spreading of the British colonial administration where once the Mughal emperors had reigned supreme. Saiyid Ahmad Khan was linked to Sufi movements working for the reform of the Muslims, but he was also close to the Delhi College, an innovative educational venture which strove to bring together British and classical Indian and Islamic knowledge through the medium of Urdu, the local vernacular. In the forties and fifties of the nineteenth century, the Delhi College became the hub not only for the training of a new generation of future administrators, but also of public debates, pamphlets and a number of journals. The revolt of 1857 saw Saiyid Ahmad Khan (and most of the men linked to the Delhi College) on the side of the British. This did not prevent the British from identifying the Muslims as the main culprits and consequently marginalize them.

For the rest of his life, the reconciliation between the colonial power and the Muslim community became the central topic of Saiyid Ahmad Khan’s life. On the one hand, he strove to explain the Muslims to their rulers and to warn them about the effects actions might have, which did not take into consideration the sentiments and the honor of their subjects. On the other hand, his goal was to educate and reform the Muslim community. This implied overcoming their resistance to Western knowledge by showing that the word of God, as it was revealed in the Quran, and the work of God, as explained by modern science, could never contradict each other. It also implied a passionate struggle for reforming the life style of the Muslims, imparting new values – not least a desire for well-planned allocation of resources and avoiding the waste of money and time. These values have often been identified as Victorian, but they can also be shown to have a genealogy in Sufi reformism.

Saiyid Ahmad Khan created two institutions to further his program. The first was the Muhammadan Anglo Oriental College at Aligarh, a small town, some 200 km south of Delhi. It was built as a residential college for the social elite of the Muslims after the model of Oxford and Cambridge, in which they were trained to become the future leaders of the community, in English and under the guidance of a British principal. The second was the Urdu journal Tahzib ul Akhlaq, translated on the title page as The Muhammadan Social Reformer. It is in this journal that the article "Bygone Time" was first published. Its readership consisted of men interested in the reform of the Muslim community and in the debates on the education of the young generation. Published from Aligarh, the journal reached readers all over north India, not only in the larger cities, but also in the many townships, where the Muslim gentry had lived for centuries.

The old man of the essay "Bygone Time" is a figure within a story that is created by Saiyid Ahmad Khan to communicate a message to the audience. It therefore relies on a shared knowledge of how emotions arise and how they are experienced. Why did Saiyid Ahmad Khan choose the narrative form of a dream to convey the particular experience and emotional reaction to time?

Dreams were an important part of religious, personal and literary life in Saiyid Ahmad Khan’s times and milieu. When Saiyid Ahmad Khan sent transcripts of his own dreams to his friend and biographer, he states that his interest was sparked by his interpretation of a famous religious story: of Joseph’s dreams in Egypt, as they are recounted in the Quran as much as in the bible. Saiyid Ahmad Khan’s own dreams were not integrated into his biography. The reason was probably that their main topics – religious affiliations to Sufi masters or fantastic threats and deaths – did not fit the rationalist outlook his biographer was to convey.

But as not a "real" but a literary dream, "Bygone Time" follows different rules and possibilities. While Saiyid Ahmad Khan’s own dreams do not entail emotional responses to what happens, but are presented in the form of immediate pictures of his dream experience, the dream in "Bygone Time" dwells on the old man’s emotions in detail and according to specific literary conventions. The sadness and terror the old man feels when thinking about his bygone life are dramatized, externalized and universalized by mirroring (and being mirrored in) the thunderstorm that rages in front of the open window. A similar correspondence between emotions and natural phenomena was known to the audience from another widespread literary genre, the Barahmasa. Here, the longing for the departed lover are described throughout the twelve months of the year, paralleling each month’s characteristics in weather, flora and fauna.

However, while both Barahmasa and "Bygone Time" both have a happy ending, their time structure could not be more different otherwise. The storm does not structure the old man’s feeling in a cyclical manner as do the recurring seasons in the Barahmasa. As the old man’s emotions, so does the storm react to each phase of his life that the old man remembers, from childhood, via youth to his middle age. The readers follow the emotional reactions to the passing of time. The appearance of the goodness calms nature’s upheaval and temporarily instills hope in the old man, but there is no future event that is to resolve the old man’s despair and anxiety: neither is there an arrival of the lover as in the Barahmasa, nor the expectation of paradise as in religious salvific narratives. The good that the old man longs for can only be reached during his life on earth, and one of its major qualities is that it endures in this world.

Indeed, time itself is what evokes most emotions. The most dramatic exclamations of the old man address time and express his newly discovered emotions towards it: "Oh time, oh time! Bygone time! Alas! What a pity that I remembered you all too late!", or: "how could I waste you!" His friends and family members, too, express their sorrow towards the bygone time by crying out their eyes and bite on their fingers in distress, as "What can we do now (that time has passed)?" This irrefutable loss of time and the old man’s vain wishes to return to the past repeated over and over. There is a way to reach a stable ground in this fleeting time, as the personification of the everlasting goodness tells the old man, but for him personally this advice comes too late.

The story of the old man is thus characterized by gloom and despair vis-à-vis a linearly progressing and limited individual lifetime. It is the two temporal levels of the narrative – the old man’s presence and his past memories – that allow to describe this emotional reaction towards the past lifetime. Both levels remain distinct, which is quite unusual for dream narratives that often, as in Saiyid Ahmad Khan's transcripts of his own dreams, collapse various time layers and are not bound to chronology. For most of the story, there is actually no reason to perceive of the old man’s story as a dream, as it lacks the usual initial framing narrating how the protagonist falls asleep. The end of the dream is remarkable, too. There is a sudden rift. The old man loses consciousness, a commonplace of lament and severe pain. However, he never gains consciousness again, but is superseded by the boy. This emphatic disjuncture between two thinking and feeling subjects introduces yet another level of narration that retrospectively sets everything that happened before in a "dream-world" – which is not framed by psychoanalysis, though, but still very much conveys a warning from the other world, as in Prophetic dreams.

For the emotional reception of the story, the temporal structure of the narration is decisive. The pain of the old man can be witnessed by the readers without knowing that this is "only" a dream and the irreversible consequence of his past mistakes can be drawn relentlessly. The dream allows the readers to track individual becoming along stages of development and makes them perceive of time as something irreversible. Even the quasi-divine figure of the everlasting goodness cannot reverse it. It is a one-time chance that people have to make use of their time. Nevertheless, the story can end on an optimistic and future-oriented note when it depicts the joy of the boy – the first reader of the dream narrative who is to be emulated by the readers of "Bygone Time" at large. This allows for a unique emotional reaction of the readers, who move from sadness and despair about an irreversibly lost past to a sudden and unexpected hope in a still possible future.

The simultaneous restriction of what one can do to time and the extension of its emotional value is conveyed in a form that builds on established roles of dreams and at the same time transforms them. In Indian and Islamic cultural history, dreams have long since been valued as privileged access to truth. They predict the future and motivate historical persons as much as figures within narratives to change their action. In "Bygone Time", however, the two added frames at the end – the boy awakening and the author exhorting the boys of his community – are very brief, thus corresponding to the omission of a framing narrative in the beginning. They do not leave room to depict a consequential change in the boy’s action, who merely reacts by rejoicing that he had ‘only’ been dreaming and subscribes to his mother’s call not to end up as the old man did. His resultant action is that he commits himself to shape his own future, and it is this commitment that the authorial voice, in the last paragraph, urges the "youthful compatriots" and "children of the community" to mimic. What making use of one’s time and doing good to the fellow humans means is not determined within the narrative and has to be concretized by the readers.

"Bygone Time" is thus embedded in a larger dream culture that includes valuing individual dreams in "real-life" and as part of religious beliefs as much as narrated dreams. The latter were, for example, part of the Persian romances that formed part of the educational canon. But "Bygone Time" is also an early example of the revaluation of dream narratives, which, far from being mutilated in colonial modernity, became crucial in many important (reformist) novels. Early Urdu novels, for example, continue the use of dreams to drive forward the plot by creating an outlook into the future, and to offer windows into the inner life of the protagonists. At the same time, they combine these with "novel" techniques of detailed fictionalized depictions of interiority and, as in "Bygone Time", of fast switches between different time layers. They thereby offer possibilities for new emotional experiences, not the least ones related to time. In "Bygone Time", the dream does not primarily convey a truth that is to be followed, but provides a testing ground for one possible future. That this testing is effective to persuade the boy – and with him the readers – to seek other alternatives to a great extent relies on the detailed depiction of the emotional experience of the old man.

The dream thus needs to be read against the larger context of the transformations marking the life of Muslims in colonial India. The old values are no longer sufficient, Saiyid Ahmad Khan aimed at showing. In his middle age, the old man had been a pious Muslim, keeping the fast, praying regularly, going for pilgrimage and paying zakat, the yearly Islamic charity. More than that, he also spent money on pious projects and consulted with saints and religious leaders. But none of this would remain, the dream showed, and save him from the angst of the fleeting time: the hungry would become hungry again, and his life on earth would vanish without a trace. Nostalgia, longing for the time gone bye, thus is no longer a bitter-sweet feeling, in which to indulge in poetry and in the company of friends, but has been transformed into a lonely form of despair, which should not be cultivated but is the sign of a life misspent.

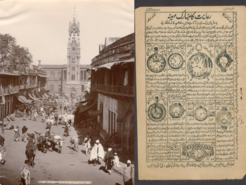

It is only the apparition of the eternal virtue, which instils calm in the old man’s heart: nothing but performing his duties towards God and men, and acting for the well-being of the community, without an eye on reward, can anchor him in time and grant him a semblance of eternity. But this salvation cannot be reached at the spur of a moment, when life is almost over. Time has become a precious good, which cannot be recovered once it is lost. From youth onwards, saving time and carefully planning how to spend it, thus becomes of central importance. This new time regime has been linked to colonial modernity – its most visible symbols being the clock towers, which became defining features of Indian cities since the 1860s and the dissemination of watches, which were increasingly advertised in journals as objects needed by and marking out the modern man.

Time was just one factor, which the dream shows in a new relation to pious emotions – no longer in the hands of God and his mercy, but given over to man to make well-planned use of. The same holds true for virtues. The five pillars of Islam, which anchored the faithful in this world and the next, have become part of the effervescent, which no longer guarantees man’s place. They are not necessarily replaced, but complemented and reinterpreted by virtues directed no longer towards God in the first instance, but towards men, and, most importantly, towards the community of believers. If this shift of virtues and emotions from the afterworld to this world and from God to man can be called secularization, it would be a secularization of a very particular kind. In the dream the eternal virtue does indeed take the place traditionally reserved to either the Prophet or a saint, as messenger of God, but also as the object towards which the intense feelings of love and longing are directed. But at the same time, it is virtue’s very anthropomorphization as the Beloved which re-enfolds the changes within the traditional imagery. More, the old man in the dream is clearly marked out as a Muslim. It is not by taking his distance from inherited piety that he would achieve salvation, but by going for its deeper meaning. The love of God is no longer sufficient by itself and needs to be substantiated and embodied in caring for the well-being of God’s creatures, above all the community of the Muslims – the central topic of Saiyid Ahmad Khan’s reformist program, as we have seen above. This neither privatizes religious feelings and beliefs, nor does it marginalize the role of religion in the arousing emotions. It is through passionate emotions that the community of Muslims is saved from its impending doom.

From this it already becomes obvious that reading colonial modernity only as a project of disciplining emotions might not be doing justice to the complexity of the transformations. The inexorable movement of linear time and the new time management it gives rise to certainly can be linked to the spreading of global capitalism and the new value it gives to time. It can also be interpreted as curbing spontaneous emotional exuberance and allocating to it specific times and spaces. But time itself, as the dream shows, has become an object of violent emotions. Modernity brings with it an increase in man’s responsibility. Not only has he to bring about his own salvation and save the community through reform, but he has to do so without being able to rely on the help of miraculous interventions by God or his saints (however, the dream also shows that praying God for his help remains important). But not all the emotions linked to time are negative: time is also becoming the object of intense longing. Without completely dislodging paradise, salvation is transposed into the future and brought down to earth – it is in what man does for his community that he will achieve eternity.