The Executioner as Tabloid Author

Conscious and Unconsious Performance of Emotions

by Joel F. Harrington

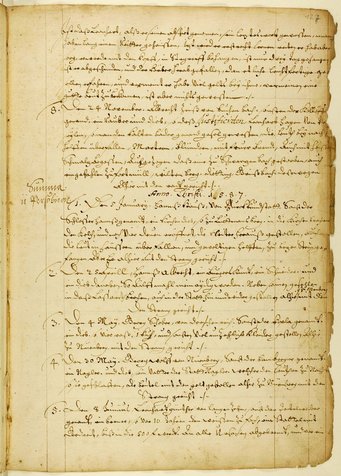

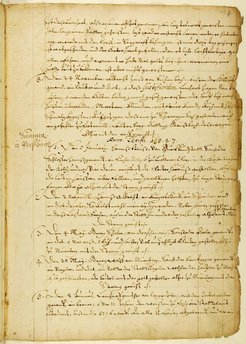

Frantz Schmidt (1554-1634), better known as Meister Frantz, served as executioner for the imperial city of Nuremberg for forty-five years, during which time he executed 394 individuals and tortured or flogged many hundreds more. He is best known to us today because he kept a journal of all this professional activity. I've used this manuscript as the principal source for a biographical portrait of the longtime executioner and his times,1 but until now have refrained from discussing Meister Frantz as an author. Yet there is much to say on this subject, despite the brevity of most of his journal entries and his ostensibly private audience, namely his city council employers. As he grew older, the veteran executioner included ever more narrative detail of his victims' crimes, occasionally resulting in short stories of a few pages. Local chronicles and picaresque literature clearly influenced his own literary formulations. But when it came to emotional language and techniques, there was no more obvious model for the executioner-author than contemporary "tabloid" accounts of condemned criminals' deeds and punishments.

Popular crime narratives were ubiquitous in Schmidt’s world: costing at most a few pfennig and hawked at the marketplace, door-to-door, in stalls, and at church courtyards on Sundays and feast days. Almost always illustrated with at least one dramatic woodcut, broadsheets often were sold with some coloration added, particularly red ink dramatizing the tantalizing bloody scenes.2 Frantz Schmidt's lifetime corresponded to the golden era of this particular genre, which had already begun to decline by the time of his 1618 retirement.3 Accounts of marauding robber gangs and their atrocities or shocking stories of domestic murders, especially of children, all enhanced the general level of social anxiety and sense of moral decay.4 They also sold copies. The unapologetically sensationalist approach of "true crime" writers - often clerics with a didactic purpose - relied on blood and gore to attract readers who would otherwise be unlikely to buy a sermon on the dangers of drink and loose living. Evil temptation and occasionally divine forgiveness shaped the overall narrative, with a text comprised mostly of detailed descriptions of both crimes and punishments.

The executioner's appropriation of tabloids' sensationalist techniques presents an interesting opportunity for historians of emotions, who face many obstacles in distinguishing between "real" experienced emotions and the performative conventions of written works, particularly for the pre-modern period. Schmidt's journal, written as much for himself as for his tiny private audience, has the potential to break through to the executioner's personal reactions to the crimes he describes. His apparently unconscious emulation of tabloid literature is not slavish, but rather simultaneously more restrained and more revealing than popular publications. Freed from concerns about manipulating his audience’s emotional responses - largely irrelevant for his purposes - the executioner author offers us a link between the normative moral narrative of early modern crime - what William Reddy might call "the emotional regime" of his milieu - and the individual interiority of the executioner himself.5

Like its tabloid counterparts, Schmidt's journal employed sensationalist techniques to create empathy for the victims of crime. Far from a modern "found" emotion,6 the ability to vicariously experience sympathy and pity for others' suffering - as well as horror and recoiling in the instance of perpetrators - was a narrative foundation of early modern broadsheets. In addition to serving the author's moral purpose (and selling copy) this technique had an effect that likewise appealed to law enforcement officials, such as Meister Frantz. As Joy Wiltenberg observes, "by drawing on common emotive response to horrific violations of life, sensational accounts eased acceptance of punitive powers and of associated moral imperatives."7 An entry from Schmidt provides an explicit illustration of sensationalist detail:

Georg Franck from Poppenreuth, a smith's man and a soldier… persuaded Fair Annie to let him escort her to meet Martin Schönherlin, her betrothed, at Bruck on the Leuth in Hungary. When he, with Christoph Frisch, also a mercenary, had brought her into a wood - the two having made a plot [about her] - Christoph struck her on the head with a stake from behind, so that she fell, then dealt two more blows as she lay there. Franck also struck her once or twice. They then cut her throat, stripped her of everything except her shift, and left her lying there, selling the clothes at Durn Hembach for 5 florins. All of this happened on St. Andrew's day [November 30] in the year '93… Executed here with the wheel, first both arms, the third stroke on the chest, as decreed.8

But whereas published accounts of violent crimes often relied on florid adjectives and other evocative language to create empathy, the staid Meister Frantz eschewed emotionally-charged language for a simple, bare bones narrative. Broadsheet staples such as grewlich (horrible), jämmerlich (lamentable), and erschrocklich (shocking) each make only one appearance in the entire journal. Grausam (dreadful) appears twice, but other dramatic favorites - such as abscheulich (abomimable), trawrig (grievous), kläglich (pitiful), orunerhört (unheard-of) - remain entirely absent.9 Schmidt also avoids the sensationalist device of re-creating dialogue or even internal thoughts, providing direct quotations only on rare occasions.10 Finally, the journal contains no explicit references to the devil or diabolic temptation, except when mentioned by one of the arrested culprits.11

One possible explanation for this restraint lies in the context of Schmidt's storytelling, namely his special audience. Generating sympathy for the victims of violence was irrelevant to his purpose, namely convincing his employers' of his long and dutiful service so that they might restore his familial honor. Another interpretation might suggest a certain emotional callousness, or at least opaqueness, is to be expected in a veteran executioner. Upon closer examination, however, we see that the seemingly dry accounts of Meister Frantz nonetheless represent unguarded moral accounts with muted or implicit emotional responses of his own.

Schmidt frequently returns, for instance, to several literary themes in his accounts of violent perpetrators and victims. He also relies on stereotypical character traits to denote his own sympathy or antipathy. In the case of the latter, cruel, treacherous, and unrepentant robbers receive far more attention in the journal than any other type of culprit. These were the asocial individuals who terrified Schmidt and his contemporaries more than any other, including alleged witches, and consequently the culprits who received the most severe punishments if caught.12 The journal's very first entry of more than three lines is description of three murders by Kloss Renkhart, including a home invasion where Renkhart killed a miller, raped his widow and her maid, then forced them both to fry and eat an egg on the body of the woman's murdered husband. This is also one of young Frantz's first executions with the wheel, a prolonged and gruesome ordeal for the executioner as well as his victim. Should we be surprised that such cases preoccupied the executioner-author throughout his long career?

Yet once more, the executioner-author rarely feels the need to characterize the brutal violence of robbers as "cruel" or "horrific". Instead, he relies on the vivid details of their attacks: the weapons used, the number of blows administered, the wounds of the victims, and so forth.13 In a lengthy account of the misdeeds of robbers Heinrich Hausmann and Georg Müllner, aka Lean George, we learn of a Jew at Niederndorf, who was shot by Heinrich and then knocked on the head by Lean Georg so that he fell over a bench and died, how Müllner cut the throat of one former associate and the next day murdered the same's wife in a little wood between Rohr and Allersberg, suffocating her with a kerchief she had round her neck, later ambush[ed] an old man in his house at night, cutting his throat and robbing and murdering him.14 Home invasions were often the most gratuitously violent attacks, yet here even Meister Frantz tended to pull back from too many details, summarizing robbers' prolonged debauchery as binding [their victims], torturing them, and doing violence to them.15 Only the atrocity of carving live fetuses out of pregnant women and cutting off their hands - a stock and perhaps fantastic abomination in popular literature - triggers emotionally-laden terms, such as references to the victims' "little hands" or "little throats" (which the robbers slashed).16

Describing acts of violence, of course, does not in itself reveal the nature or depth of Schmidt's own unspoken emotional responses. Here we must turn to his reliance on sensationalist literature's complementary effect conveying the sheer terror experienced by the victims of such violence. Once more, the home invasion promised an especially powerful vicarious experience, as in Schmidt’s re-creation of the night that maid Anna Maria Haisin let two accomplices into the house of her employer, the elderly and wealthy "Virgin Plobin," and left the door open to the chamber where the virgin lay, whereupon they fell on her and wretchedly smothered her with two pillows over her mouth, which lasted almost a half hour, [the virgin] struggling so that they had [to smother her] three times before she died.17 Shifting to even more sympathetic victims, Meister Frantz describes how the robber Georg Taucher broke into a house and murdered a tavern keeper's son … cutting his neck and throat, [and] tak[ing] money from the till, or how the notorious Georg Müllner and his companions invaded a farmer's house at night, cut his throat, and attack[ed] the same farmer's son (whom the father had hidden in the oven), stabbing him in the thigh and stealing much, so that the farmer's son died eight days later.18

Meister Frantz's openly fierce responses to all attacks on children suggest we have clearly moved beyond imitated technique to the author's own emotional responses. Amid the otherwise laconic entries of his early days, Frantz carefully details the thoroughly reprehensible assault of Hans Müllner (aka the Molder), who raped a girl of thirteen years of age, filling her mouth with sand so that she might not cry out. His shock at a similar betrayal of childish trust by Endres Feuerstein is conveyed by listing the respective ages of the five girls the young man raped at his father's private school (six, seven, eight, nine, and twelve) and pointedly adding that two among them he damaged so [severely] that one could no longer hold any water [and] the city midwives nursed [another] for a long time, believing she would die.19 Most jarringly, he reports the especially brutal attack by fifteen-year-old Hanns Wadl on an eleven-year old girl collecting wood, [throwing] her to the ground and attempt[ing] to bring her to his will. When the girl screamed and said she was too young, he replied "By the sacrament, you have a good sturdy cunt." Throughout her mighty screaming [he] held the girl's mouth shut, drew out his knife, [and said] if she would not stop he would stab her, thereupon knocking the girl around, so that two barbers were [later] needed. Also made the girl swear not to tell anyone - not even the devil - anything of it.20 As in the popular press, details about young victims, their wounds, and their suffering all lend emotional resonance to acts of violence - again more explicitly than any other accounts in the journal.21

Violence against children in any form was hard enough for Meister Frantz to forgive; violence against one's own flesh and blood remained utterly incomprehensible and unpardonable to him. Throughout his long career, Frantz would execute twenty women for infanticide; in every instance he showed himself especially sensitive to the suffering of the young victim. Most commonly, he refers to the mother squeez[ing] [the child's] little neck, or crushing the little head, and in one instance murderously stabb[ing] [the male child] with a knife in the left breast.22 As in Frantz's descriptions of vicious robbers, the contrast of innocence and brutality is a topos borrowed from true crime literature. He vividly recreates how Dorothea Meüllin stopped up the mouth with earth and made a grave with her hand in which she buried the struggling child, or how Margaretha Marrantin gave birth during the night near a shed by the river Pegnitz and as soon as [the child] stirred its arms and struggled, she threw it into the water and drowned it. Other equally disturbing means of disposal included burying in a barn, locking in a trunk, casting into a heap of garbage or, most shocking, throwing alive into the privy.23 Perhaps Schmidt's most heart-wrenching re-creation of the moment of death came in the case of Veronica Köllin, who having conceived a child with a farmhand, gave birth to the same in her brother's (Hans Kohl's) pond-house, which was a girl, and [when it] squealed a little, supposing her brother's wife who was in the kitchen might hear it, she held its mouth with two fingers. When she took her fingers away, made two more little squeezes, thus suffocating it. When she attempted to bury it early in the morning, a washerwoman saw her and the deed became known.24

Frantz Schmidt's selective appropriation of tabloid techniques for evoking and provoking such emotional responses speaks less to his identity as an author than as a feeling individual himself. Like his published counterparts, he sees his stories in explicitly moral terms. Unlike them, his portrayal of violent criminals and victims serves no didactic purpose. The great majority of his accounts are not embellished with telltale adverbs and adjectives but with narrative "facts" - facts which he arranges to convey his own empathy, not convince his employer readers. He obviously draws on the emotional conventions of his day, "like notes in a [musical] scale" in Barbara Rosenwein's words,25 but the composition he produces remains one of unexpected self-revelation.

Notes

1 The Faithful Executioner: Life and Death, Honor and Shame in the Turbulent Sixteenth Century (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2013).

2 Joy Wiltenberg, Crime and Culture in Early Modern Germany (Charlottesville & London: University of Virginia Press, 2012), 9-12. Wiltenberg's work provides the single best introduction to this fascinating genre. See also her Disorderly Women and Female Power in the Street Literature in Early Modern England and Germany (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1992).

3 In addition to individual specimens throughout European archives and libraries, see the collections of Johann Wick from the 1570s and 1580s of Georg Philipp Harsdörfer, a Nuremberg patrician, during the mid-seventeenth century. Wiltenberg, Crime and Culture, 17.

4 Wiltenberg, Crime and Culture, 115ff.

5 I'm grateful to Laura Kounine for sharing with me Jan Plamper, "The History of Emotions: An Interview with William Reddy, Barbara Rosenwein, and Peter Stearns," in History and Theory (May 2010), 237-65.

6 Cf. Ute Frevert, Emotions in History—Lost and Found (Budapest/New York: Central European University Press, 2011), 12.

7 Wiltenberg, Crime and Culture, 161. See especially 136ff. on this topic.

8 Frantz Schmidt's Journal, Stadtbibliothek Nürnberg, Amb 652.2°, in the following FSJ Mar 271595.

9 FSJ Jul 15 1585; Jan 16 1616; Jul 6 1592; Feb 10 1596; Feb 9 1598.

10 FSJ Feb 18 1585; Mar 15 1597; Mar 16 1585; Nov 14 1598.

11 FSJ Feb 8 1598; Jul 8 1613; Jan 25 1614; Feb 18, 1585; Jan 19, 1587; Jan 2 1588.

12 See, for instance FSJ 1577; July 15 1580; May 25 1581; Feb 20 1582; Mar 17 1584; Jan 2 1588; Feb 10 1596;Jul 4 1588; Jun 21 1593; Jul 11 1598.This theme was also prominent in crime literature of the era (Wiltenberg, Crime and Culture, 31ff.). On early modern popular perceptions of robbers and organized crime, see Richard J. Evans, The German underworld: deviants and outcasts in German history (London/New York: Routledge, 1988), 2ff; also Carsten Küther, Menschen auf der Strasse: vagierende Unterschichten in Bayern, Franken und Schwaben in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1983), 60-73; and Florike Egmond, Underworlds: organized crime in the Netherlands, 1650-1800 (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993), especially 37ff.

13 Wiltenberg, Crime and Culture, 125ff.

15 FSJ May 25 1581. See also Feb 20 1582; Jan 5 1587; May 25 1581.

16 FSJ 1577; Jan 2 1588; Apr 21 1601; Bastian Grübel also supposedly stole children and offered them for sale to the Jews. Ulrich Oettingen supposedly killed 25 people in the Nuremberg area around same time, but the most famous mass murderer of the day was Christman Genipperteinga, alleged to have killed 944 people in thirteen years. Wiltenberg, Crime and Culture, 32, 97-98, and see 127-130 on the disemboweling of pregnant women.

18 FSJ Apr 28 1579; Jun 21 1593. See also Feb 28 1615.

19 FSJ Jul 23 1578; Jun 23 1612. See also May 2 1579; Apr 10 1582; Jun 4 1599.

21 On the disproportionate number of family killings in the popular press, see Wiltenberg, Crime and Culture, 36, 131-33.

22 FSJ Mar 6 1578; Jul 13 1579; Jan 26 1580; Feb 29 1580; Aug 14 1582; May 5 1590; Jul 7 1590; Mar 15 1597; May 20 1600; Apr 21 1601; Aug 4 1607; Mar 5 1616.

23 Jan 26 1580; May 5 1590; Jul 7 1590; Jun 26 1606; Feb 8 1614.